Chatbot for BI walkthrough

In this blog post, I will guide you through the code for baldrick, a chatbot for business intelligence (BI). This article is aimed at anyone interested in building a large language model (LLM) powered application, or those curious about using GPT to write SQL.

Baldrick is an LLM-powered chatbot that resides in Slack and queries BigQuery for data. It was built from scratch in Python using GPT-3.5-turbo as its primary LLM backend. I chose to specialize it for the activity schema, as I regularly use it for user journey and product analytics in my day job (data science, analytics, engineering consulting).

The User Experience

When building applications, we should always focus on the user experience. If an application isn’t easy to use or helpful in solving a problem, it’s not worth creating.

For this use case, the ideal user persona is a business user—someone on the executive team, in sales, business development, or anyone who needs data to make decisions without regularly using SQL. These users often spend a lot of time on Slack (or another team communication platform) and don’t want to introduce another tool to their routine.

Their ideal workflow involves opening a Slack channel, asking a question (e.g., “How many widgets did we sell last month?” or “When was the last time someone from Acmesoft logged in?” or “Show me a weekly-cohorted retention analysis for my chatbot, Baldrick”), and receiving a correct answer accompanied by an explanation of what the answer means.

|

|---|

| Asking Baldrick a question |

One concern is that this workflow may feel a bit like magic. If a business user asks a question and gets an answer, how can they verify its correctness? Simply showing the SQL query used to obtain the answer is insufficient. Even if they know some SQL, they might not understand the data in the data warehouse well enough to know if everything is accurate. Or, they might know the data sources but lack sufficient SQL knowledge to discern if the query is formed correctly.

To address this, we present the query plan, explain its functionality in natural language, obtain the answer, and display the results inline. While explaining the query in natural language may not allow users to catch all errors, it should provide enough information for them to consult others and verify the data sources’ accuracy.

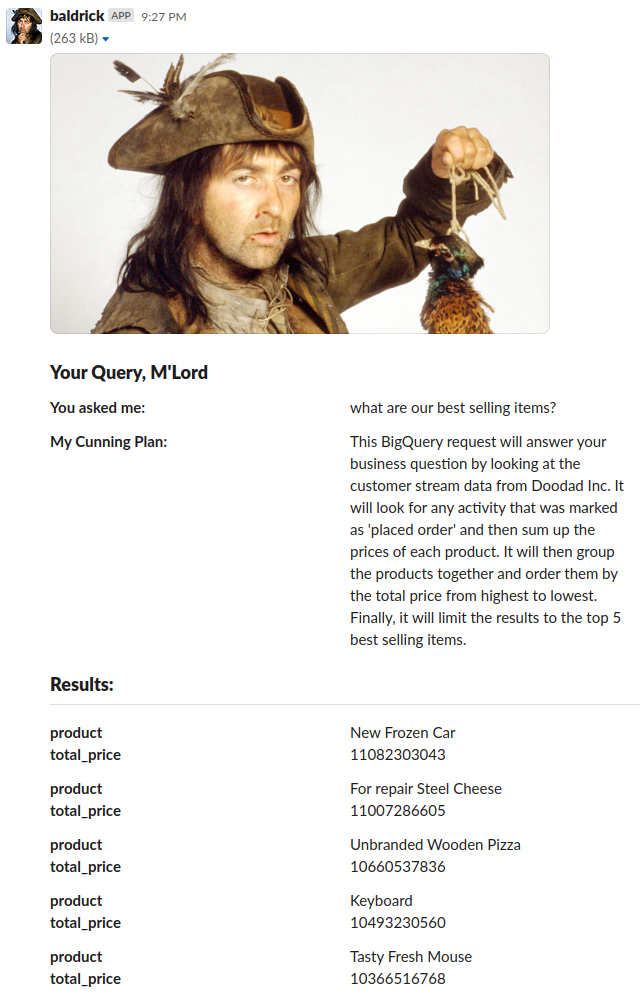

|

|---|

| Baldrick giving you an answer |

After displaying the answer and explanation, several buttons are available for feedback.

|

|---|

| Baldrick getting feedback for improving the service (RFHL, and in-context learning) |

Users can view the SQL to copy, paste, or inspect it, whether they are familiar with SQL or wish to open a support ticket.

Additionally, users can choose to give a thumbs up or thumbs down on the results. This feedback is useful for directing potential support issues to an analyst on the team and improving the chatbot’s quality. I will discuss the feedback loop later in this post.

Application Overview

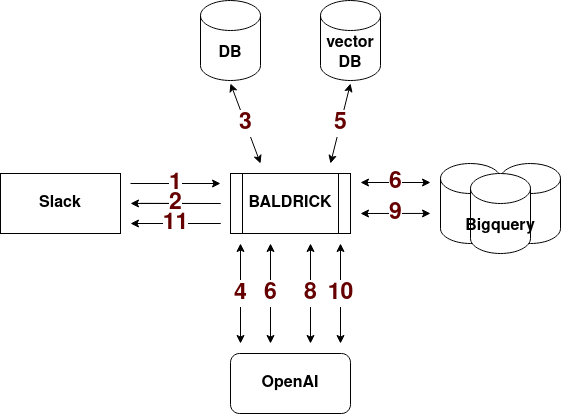

|

|---|

| Baldrick Data Flow diagram |

The workflow consists of several steps:

-

A slash command in Slack sends the user’s request to Baldrick.

-

Baldrick acknowledges the command by sending a message back to Slack. The message repeats the query and reassures the user that it has “a cunning plan.”

-

We gather all relevant activities for the business question from the database. In the activity schema, obtaining the activities is similar to acquiring all relevant tables in “normal” data warehouse schema.

-

We form a prompt with all of the candidate activities and send it to the LLM to choose the ones that are relevant for the business query.

-

Next we get the parts needed for in-context learning (previous examples used to help the LLM know what we’re trying to do). We take the business question the user asked and look to see if we’ve answered similar questions in the past. We find the ones that are most relevant and get the business question and SQL used to answer it.

-

Next we form the prompt explored below. We provide the LLM with the schema for each activity, similar business question-SQL pairs pulled from Baldricks chat history, and the current business question. This prompt returns the SQL query to be used to answer the business question.

-

We check the query validity by running it through the planner. If the plan comes back without an error, the SQL is valid.

-

If the SQL fails the query planner, we attempt to fix it once. We pass the business question, the SQL, and the error to the LLM and ask it to correct the query. If that also fails, then we apologize to the user, log the query, and end the process.

-

We run the query and obtain the result.

-

The next prompt uses the business question, query, and result to explain everything in terms a business user can understand.

-

We send the query, explanation, and results back to Slack, where they are formatted in an attractive text block for users to review.

-

[Optional] The user can choose to view the query and upvote or downvote the answer. These options are implemented using buttons in the Slack app. Responses are recorded alongside the business question, SQL, and some metadata in a database for future use in prompts and for RFHL learning.

The entire app is built on GCP and deployed to a Google Cloud Run function. I set up a workload_identity_provider to securely push the code to Google Cloud Build using a GitHub action, store it on the Artifact Registry, and then deploy it to Cloud Run.

A Deep Dive Example

I want to provide a detailed examination of a single LLM prompt, focusing on how we generate the inputs and parse the output. I’ll use the function responsible for generating an SQL query using the activity schemas and some example queries (GitHub code).

The Prompt

Here is the prompt template:

Given an input question, first create a syntactically correct BigQuery query to run.

Only use the following table:

{table_info}

where the activity is one of these strings: {', '.join(self.activities)}

and the JSON schema for each of these activities is:

{self.valid_activity_schema}

Double check that your query obeys the following rules.

- You can order the results by a relevant column to return the most interesting examples in the database.

- Unless the user specifies a specific number of examples, always limit your query to at most {top_k} results using the LIMIT clause.

- When performing aggregations like COUNT, SUM, MAX, MIN, or MEAN rename the column to something descriptive

- Use valid BigQuery syntax

- Use JSON_QUERY(feature_json, '$.json_path') to access fields in the activity JSON.

- Account for possible capitalization in in STRING values by casting them to lower case.

- All queries should be FROM {fully_qualified_table_name}

- If the user wants to limit the time range for the question use CAST(ts as DATE) and CURRENT_DATE() appropriately in the where clause.

Examples:

{ self.examples }

Question: {self.user_question}

BigQuery Statement:

We pass the prompt template all of the inputs and then receive the string for OpenAI to evaluate.

An example of the template with all fields filled in is:

Given an input question, first create a syntactically correct BigQuery query to run.

Only use the following table:

TABLE activities (

activity_id text,

ts timestamp,

customer_id text,

activity text,

anonymous_id text,

feature_json object

)

where the activity is one of these strings: sale, pageview

and the JSON schema for each of these activities is:

ACTIVITY sale (

url text,

item_name text,

item_price decimal,

quantity int,

)

ACTIVITY pageview (

url text,

manual bool

)

Double check that your query obeys the following rules.

- You can order the results by a relevant column to return the most interesting examples in the database.

- Unless the user specifies a specific number of examples, always limit your query to at most 5 results using the LIMIT clause.

- When performing aggregations like COUNT, SUM, MAX, MIN, or MEAN rename the column to something descriptive

- Use valid BigQuery syntax

- Use JSON_QUERY(feature_json, '$.json_path') to access fields in the activity JSON.

- Account for possible capitalization in in STRING values by casting them to lower case.

- All queries should be FROM ANALYTICS.ANALYTICS.ACTIVITIES

- If the user wants to limit the time range for the question use CAST(ts as DATE) and CURRENT_DATE() appropriately in the where clause.

Examples:

Question: How many widgets did we sell today

BigQuery Statement: select count(*) from ANALYTICS.ANALYTICS.ACTIVITIES where CAST(ts as DATE) = CURRENT_DATE()

and activity="sale"

and JSON_QUERY(feature_json, '$.item_name')="widget"

Question: How many pageviews did we get today

BigQuery Statement: select count(*) from ANALYTICS.ANALYTICS.ACTIVITIES where CAST(ts as DATE) = CURRENT_DATE()

and activity="pageview"

Question: How many sales per pageview have we gotten for the last 5 days?

BigQuery Statement:

There are a few things to notice here:

- The schema at the beginning is reinforced by the examples. The LLM has the opportunity to see the schema and query syntax several times in the prompt, which seems to help it create better SQL. Without the in-context part, the LLM would generate errors at least 20% of the time. Adding the examples significantly improved this.

- Over time, we noticed the same types of errors appearing. We had to expand the list of errors each time a new one emerged. For some trickier errors, they could not be resolved until we added the examples.

- The examples should be formatted exactly like the end of your prompt. This is the most effective way to get the LLM output to match your desired output.

- This was created before OpenAI refactored the API to accept a list of messages. Today, I would include the first line in the system message along with more specific instructions about the desired behavior.

Embeddings and Similarity

I experimented with several different embedding libraries, both paid and free. For this application, the choice made little difference (though it can be significant for other applications). I selected sentence-transformers/all-mpnet-base-v1 from the sentence_transformers library because it was reasonably fast and has good evaluation metrics.

Here’s how the embeddings work:

- Pass the business question through the sentence_transformer, which returns a large vector.

- Store the business question and SQL query in a dictionary where the key is the embedding vector.

- When a user asks a new question, compute the embedding for that string.

- Iterate through the items() in your dictionary and compute the inner product between the new vector and the key to get the score.

- Create a list of tuples where the first element is the score and the second is the dictionary value.

- Sort that list in descending order of score and take the top K values.

In essence, this is how a vector database works.

From my experience, it’s a good rule of thumb to have a few reinforced data points but always fewer than the number of tokens the largest query might return.

Incorporating Feedback

In this application the most direct method of incorporating feedback is through inclusion of the business questions and SQL queries that have been thumbed up by users. For those queries where the results look correct, we can take the business question, compute it’s embedding and then insert it back into the vector database. In the future, if the same or a similar question is asked, the business question and SQL will be used as an example in the prompt.

A List of Learnings

LLM Applications

- Latency is your #1 challenge. Whenever new data is given to Baldrick, acknowledging it and giving the user a sense of progress is crucial. Users may abandon the query if it takes too long to compute.

- Parsing the outputs of prompts usually works, but since it doesn’t always, you need a fallback to repair broken data. I explored using the LLM itself as well as more deterministic methods, and both sometimes work.

- Running out of tokens for your output results in broken output. It’s important to count tokens and ensure you have enough left for your expected return value. I typically try to make sure the input takes less than 75% of my token count.

Using a LLM for Analytics

- Using an LLM for SQL works remarkably well. After implementing the in-context learning part, I received virtually zero errors for the returned SQL.

- Using the activity schema wasn’t a terrible choice. There are no joins, which is an advantage over other data warehouse strategies. However, it does have a different schema for each of the activity_json entities, so the complexity is still present. I imagine this complexity would increase over time since schema management in JSON tends to be pretty poor (in my experience).

- Over time, you will face problems migrating fine-tuned or in-context SQL to new schemas. Managing that dataset will likely be more challenging than for dbt or other analytics frameworks since there could be numerous different and unusual queries.

- The state of synthetic data creation is lacking. There are some tools like Faker for creating single fields, but if you want to create a synthetic dataset for a project like this, it’s not easy. There aren’t any tools that simplify this process, and even if you manage to create something with a nice schema and a rich set of events, introducing real-world correlations to generate surprising or interesting results is difficult.

Conclusions

I built this project to see if anyone was interested enough to try to get it working or modify it for their own use. While I didn’t get much interest from the community, I did receive some interest from others working in the space. Over the last few months, I’ve had 5-10 conversations with early-stage technologists and founders about how to build things like this, what I found surprising, and where it’s all heading.

It’s an exciting time to be talking to people and building new things, as there seem to be limitless possibilities. I hope this article sparked new thoughts and ideas for your own projects!